When working with colleagues and partners in Asia and emerging economies, building personal and interpersonal relationships is often a critical factor in getting things done efficiently and effectively. This stands in contrast to the idea that professionalism typically means maintaining clear boundaries between private life and work.

I have worked as an on-site manager for international development projects in seven countries across these regions over more than 20 years, and I once believed that professionalism meant clearly separating private life from work.

This is why I felt uncomfortable when local colleagues brought personal topics into business meetings. I felt embarrassed when my local staff asked me to help with his personal issues. To me, they seemed unprofessional and inefficient—as if private and business matters were being inappropriately mixed.

For example, I was part of WhatsApp groups where colleagues openly celebrated each other’s birthdays or asked whether someone could help pick up their children after work. In one Middle Eastern country, I often observed colleagues spending a significant amount of time chatting over coffee in the morning—discussing their children’s university exam results, political movements, or how and where they bought a used car.

From my perspective at that time, this looked like a waste of valuable time and resources. I believed these personal conversations directly contributed to missed deadlines, delayed reports, and unmet milestones. I saw personal relationships as an obstacle to efficient and effective project management.

However, over time, my understanding gradually changed.

Without any particular intention, I gradually became involved in these daily coffee conversations with my local colleagues and staff in one Middle Eastern country, discussing everyday matters—family updates, local news, weekend plans.

Before this shift, my tasks were often treated as low priority, deadlines were missed, and commitments were not always kept.

Yet once these informal, personal interactions became part of our daily routine, my work began to receive priority. Deadlines were respected, promises were honored, and my colleagues became far more flexible—even accommodating requests that might previously have been considered unreasonable.

I realized that what I had once dismissed as “unproductive small talk” was, in fact, a powerful mechanism for building trust and mutual commitment.

People are motivated by different things. While salary increases, promotions, or opportunities to work on large projects can be strong motivators, I learned that this is not universally true. Many of my colleagues and partners in Asia and emerging economies told me that they genuinely enjoyed coming to work because the workplace was also a place to meet friends—to work with people they trusted, cared about, and felt connected to, and to achieve something together.

In these contexts, personal relationships are not a distraction from work. They are the foundation of engagement and commitment. Once trust is established through interpersonal connections, colleagues are more willing to cooperate, more flexible in responding to requests, and more likely to go the extra mile to meet shared goals.

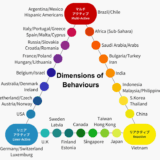

What I’ve learned is that there is no single definition of professionalism. In some cultural contexts, maintaining boundaries between personal and professional life is valued. I came to understand that, in many Asian and emerging market contexts, investing time in personal relationships is essential practice.

Understanding this difference is not about judging which approach is right or wrong. It is about recognizing that professionalism takes different forms in different cultural contexts—and that adapting to those forms is often critical for effective leadership and collaboration.